Ecosystems are not a new phenomenon. The term has existed in relation to the natural environment since 1934 when coined by British ecologist Arthur Tansley and defined as the flow of energy and material through ecological systems.

Today, the term’s usage has morphed into the digital business world where information and communication technologies blurred boundaries between producers and consumers. These blurred boundaries formed into networks of participants where shared purpose and shared leadership are the norm.

Digitization provided the opportunity for those with a common interest to collaborate rather than only compete. This fits nicely with the “business is relationships” trend that emerged over the last 100 years. When you combine this relationship-based trend with these ever-increasing networked ecosystems, extraordinary capabilities emerge throughout the business cycle of innovation, production and distribution.

In your own company you may have heard talk about how business ecosystems are enabling new product and service offerings without the need to own required resources via mergers and acquisitions. The impact of these emerging digital ecosystems is reshaping and redesigning the global economy, which has business owners taking notice.

Global networks of connection, collaboration and deep economic interdependence have emerged across multiple company, industry and national boundaries. There is not doubt these networks are fundamentally changing our society. I am hopeful this self-organizing change in the economy is exactly the disruptive innovation required to bring under control corporate greed, consumer over-consumption and socio-economic inequity.

Ecosystems have also been designed to tackle such tough social problems as poverty, pollution and disease, which are currently referred to as adaptive challenges. An adaptive challenge or “wicked” social problem exists without known solutions and challenges society’s deeply held beliefs, values and ways of working. These problems are outpacing our ability to solve them, in part because they defy sectored and national boundaries.

Given their wide-spread incidence, these issues are no longer the sole responsibility of the social environment. Businesses continue to get involved because a healthy nation and economy cannot survive in an unhealthy environment. Peter Drucker wrote in 1954, “It’s management’s … responsibility to make whatever is genuinely in the public good become the enterprise’s own self-interest.” Twenty years later, he cited companies like Sears and Ford that grew their businesses by taking on social ills.

Every single social and global issue of our day is a business opportunity in

disguise. Peter Drucker

Business gurus, Michael Porter and Mark Kramer, are in full agreement and view capitalism as the vehicle for “meeting human needs, improving efficiency, creating jobs and building wealth.”

The purpose of the corporation must be defined as creating shared value,

not just profit. Michael Porter & Mark Kramer

What Porter and Kramer mean by creating shared value goes beyond social responsibility, philanthropy and sustainability. It involves a new way of creating economic value that also addresses societal needs. Business ecosystems appear to follow this innovation as they engage a diverse set of actors to mobilize around a shared understanding or a wicked problem — for example: Unilever changing the hygiene behaviour of 1 billion people.

Although there is considerable progress, Unilever faces challenges it

cannot solve alone. To reach our goals and achieve large-scale change,

even more collaboration is needed between companies, governments,

NGOs and consumers. Among the areas where Unilever would welcome

more cross-sector collaboration are: reducing and eliminating

deforestation associated with soy, palm oil, beef, pulp and paper by 2020;

integrating hygiene behaviour change into national health policies and

education curricula; linking more smallholder farmers into food supply

chains; and building infrastructure to promote waste recycling and

recovery. Paul Polman, CEO

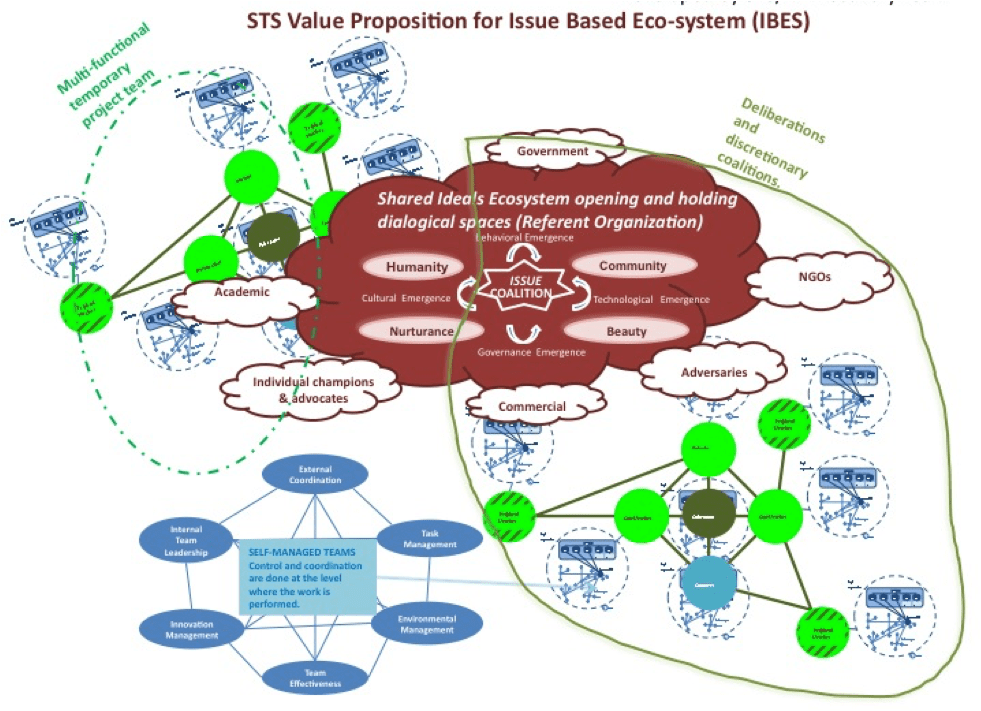

Historically, the concept of digital ecosystems reflects the maturing of both socio-technical systems thinking (STS) and supply chain management across businesses, mathematics, healthcare, global security, etc. This means of co-adapting or sharing while competing for resources brings with it key strategic and operational questions no matter the scale of the ecosystem. Of course as the number of actors increases so does the complexity of interactions.

Key questions to consider for ecosystem coordination include:

- Who is in the ecosystem?

- What are they trying to do together?

- How can they improve what they are doing?

An example of how an ecosystem works can be found in the smart mobile phone sector where these businesses grow by leveraging local complementary resources that add value for customers. The financial savings and innovative capacity are significant when compared to traditional means of accruing required resources — 1) making them internally, or 2) buying them through mergers and acquisitions.

Regardless of this new phenomenon for growing one’s business, an interesting paradox is also emerging along side ecosystems. Many large companies are shrinking the number of participants in their supply chains because their leadership fear loss of control and thus respond by bringing resources in-house. Today’s adaptive challenges, and vehicles like ecosystems that look to resolve them, demand courage to catalyze learning and change. When we continue down the ecosystem path, we move from an ownership model to a learning-resource model, which changes the strategic and operational questions.

- Who can we have relationships with that activate other peoples’ resources and talents without having to own them?

- What is the nature of the relationship (the co-creation) that adds value without ownership?

Ecosystem orchestration requires new leadership capabilities willing to draw on a range of solutions and innovations due to the diversity of participants. Digitization is forcing us, in spite of our own fearful resistance, to collaborate and co-create in community. How can this not be a good thing?

How are you currently collaborating and co-creating in your personal communities? in your business communities?

For more on business ecosystems click here.